This is volume 15 of my monthly column entitled Black Dollars Matter. As I point out each month, this column is generally designed to compel Philadelphia’s white businesses/entities and white employers to treat Black consumers and Black applicants/employees/firms with respect. But, more important, it is also designed to convince Black people in Philadelphia to “do for self” economically because money talks and BS walks.

But this month, I want to highlight a historic and essential Black organization that laid the foundation in the battle for economic rights together with civil rights.

On July 11, it will be exactly 117 years since the Niagara Movement was founded in 1905. As documented by S. Christensen at blackpast.org, “The Niagara Movement forcefully demanded equal economic [and other] opportunity … for Black men and women.”

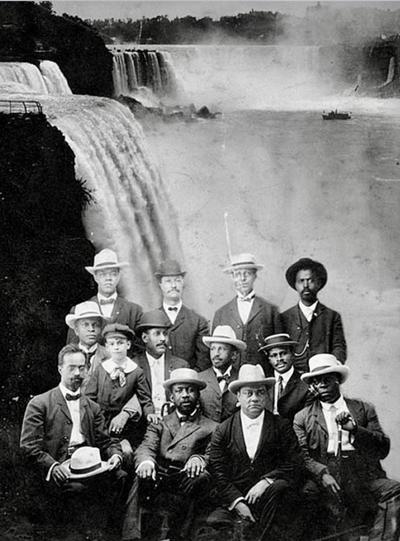

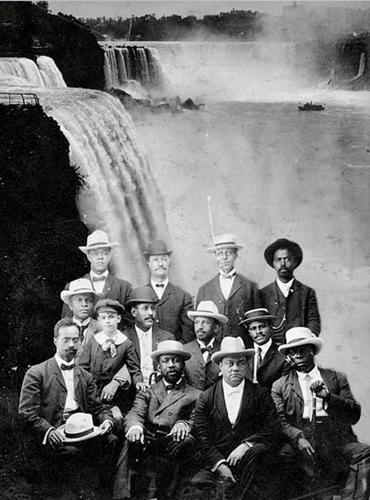

Founded by W.E.B. Du Bois- one of America’s greatest intellectual sociologists and authors- and William Monroe Trotter- one of America’s greatest intellectual anti-accommodationists and newspaper publishers- created the organization and, along with Frederick McGhee and Charles Edwin Bentley, held its first meeting with 25 other influential pro-Black activists in attendance at the Erie Beach Hotel near Niagara Falls, Ontario, Canada.

The Niagara Movement- which named itself after Niagara Falls to represent the “mighty current” of economic and civil rights change that it would bring about- rejected the strategy of the widely known Booker T. Washington who it accused of being too accommodating to racist white folks who persuaded Washington not to pursue voting rights.

In a historic 1895 speech that came to be known as the “Atlanta Compromise,” Washington- who was financed by anti-trade union robber baron industrialist multimillionaire Andrew Carnegie- said Blacks shouldn’t concern themselves with politics but only with learning a trade and creating businesses.

But the Niagara Movement members in general and Trotter in particular blasted Washington as naive and shortsighted. While they agreed with his approach to vocational training and job creation, they realized that much more was required. That’s why they also advocated for academic education and for voting rights. They took the enlightened position that without an intellectual foundation and without progressive laws created by progressive officials who were elected by Black voters, a Black person’s trade and a Black person’s business could be stolen easily without any legal or political recourse whatsoever.

Trotter’s righteous opposition to Washington was so intense that, in 1903, Trotter physically confronted him in Boston and was arrested on minor charges.

Trotter and the Niagara Movement clearly understood that financial so-called security is actually temporary if it can’t be intellectually, legally, and politically defended.

At its inaugural July 11, 1905 meeting, the Niagara Movement drafted a

“Declaration of Principles” that called for “the increase of intelligence, the buy-in of property …, the advance in literature …, and the demonstration of constructive and executive ability in the conduct of great … economic and educational institutions.”

As documented by the W.E.B. Du Bois Library at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, Niagara Movement chapters were established in 21 states a mere two months following conclusion of that July 1905 meeting.

In August of 1906, when the second meeting was held- this time in the United States at Harpers Ferry, West Virginia where “Brother” John Brown had done his thing in 1859- women were invited. And it was so successful that Du Bois described it as “one of the greatest meetings that American Negroes ever held.”

It was such a powerful meeting, such a powerful event, and such an especially powerful site that, as noted in “The Niagara Movement at Harpers Ferry” article by David T. Gilbert of the National Park Service,

“A highlight for those gathered was John Brown’s Day. It was a day devoted to honoring … [his] memory. At 6 a.m., a silent pilgrimage began to John Brown’s Fort. The members removed their shoes and socks as they tread upon the ‘hallowed ground’ where the fort stood. The assemblage then marched single-file around the fort singing … ‘John Brown’s Body.’”

During 1906, the Niagara Movement, as pointed out at history.com, “had grown to some 170 members in 34 states.” It also had “some state-level success, including lobbying against the legalization of segregated railroad cars in Massachusetts.”

Sadly, in that same year, Du Bois and Trotter had a falling out regarding the decision to allow women in the organization. Although Du Bois was for it, Trotter was initially against it but later acquiesced.

And to make matters worse, the Niagara Movement, noted history.com, could not

“gain much national momentum … [and] suffered from limited financial resources and determined opposition from [the nationally popular Booker T.] Washington and his [ardent] supporters as well as [that] internal disagreement between Du Bois and Trotter,” which caused Trotter to officially resign shortly afterward.

Du Bois led the 1907 meeting, which took place in Boston with 800 attendees and focused on ending federal Jim Crow laws. But the absence of Trotter and his backers- who together had left to found a new organization, the Negro-American Political League- was palpable.

Unfortunately, when the 1908 meeting took place in Oberlin, Ohio, the turnout was much smaller and dissension had become rampant throughout the organization.

The 1909 meeting was even smaller and attendance at the 1910 meeting, which took place at Sea Isle City, New Jersey, was so minimal that it was the last in the Niagara Movement’s history.

But the ideals of Du Bois’ and Trotter’s Niagara Movement didn’t end with its final meeting. Its ideals of economic activism in combination with political activism and educational activism were resurrected in the founding of the NAACP on Feb. 12, 1909. As highlighted on the NAACP’s website at naacp.org,

“Before becoming a founding member of NAACP, W.E.B. Du Bois was already well known as one of the foremost Black intellectuals of his era. The first Black American to earn a PhD from Harvard University, Du Bois published widely before becoming NAACP’s director of publicity and research and starting the organization’s official journal, The Crisis, in 1910 ….

He challenged the position held by Booker T. Washington … that Southern Blacks should compromise their basic rights [including voting rights] in exchange for [vocational] education ….

Under Du Bois’ guidance, the [Crisis] Journal attracted a wide readership, reaching 100,000 in 1920, and drew many new supporters to NAACP. With Du Bois as its mouthpiece, NAACP came to be known as the leading protest organization for Black Americans.”

The Niagara Movement was right in rejecting an accommodationist approach and in advocating for economic wealth backed by intellectual, voting, and political power.

You can support the Niagara Movement’s ideals, which are as important today as they were 117 years ago on July 11, 1905. And you can support those ideals in two ways.

One: Join the NAACP by logging onto https://naacp.org/join-naacp/become-member.

Two: Learn about the great Trotter by reading “Black Radical: The Life and Times of William Monroe Trotter.” It was written by a sistah named Kerri K. Greenidge who is a professor in the Department of Studies in Race, Colonialism, and Diaspora at Tufts University. She’s also the director of American Studies and co-director of the African-American Trail Project at Tuft’s Center for the Study of Race and Democracy. Her award-winning book has been described in the New York Times as a “biography that restores … Trotter to his essential place next to Douglass, Du Bois, and Malcolm X in the pantheon of American civil rights heroes.”

(0) comments

Welcome to the discussion.

Log In

Keep it Clean. Please avoid obscene, vulgar, lewd, racist or sexually-oriented language.

PLEASE TURN OFF YOUR CAPS LOCK.

Don't Threaten. Threats of harming another person will not be tolerated.

Be Truthful. Don't knowingly lie about anyone or anything.

Be Nice. No racism, sexism or any sort of -ism that is degrading to another person.

Be Proactive. Use the 'Report' link on each comment to let us know of abusive posts.

Share with Us. We'd love to hear eyewitness accounts, the history behind an article.