When the pandemic canceled shows and shut down rehearsal studios, many choreographers took to making dances over Zoom. Kyle Abraham wasn’t one of them.

He had something else in mind. Since founding his Brooklyn-based company, A.I.M., in 2006, Abraham has made works for the New York City Ballet, Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater and Paul Taylor Dance Company; he’s crafted pieces for ballerinas Wendy Whelan and Misty Copeland. But in 2020, the choreographer was profoundly uninterested in Zoom dances. He wanted to make “honest connections.” He wanted to talk.

Abraham’s newest piece, “An Untitled Love,” was not quite finished at that point. During those months of isolation, he and his dancers worked out the kinks in an unusual way: in weekly two-hour discussions, not about the choreography on its own, but about movies. And television.

They discovered that, at a time when everyday people-watching wasn’t possible, the screenings helped the performers find their characters and avoid stereotypes.

“I don’t like Zoom rehearsals. They’re really a challenge for me,” said the 44-year-old Abraham, “because I’m not an extroverted person. So I took advantage of what I enjoy most in rehearsals, where we sit and talk and dive into what we’re making and why we’re making it.”

There was no dancing. No awkward rehearsals with performers dodging their coffee tables and cats while the choreographer shouts counts at his screen. Instead, the choreographer and his cast of 10 curled up with their laptops for group conversations.

It was more like a book club than rehearsal, with dancers taking turns assigning what to watch before the next meeting. The shows and movies centered on Black characters and stories. The group hashed out episode eight of “Watchmen.” They delved into anti-trans violence in “The Death and Life of Marsha P. Johnson,” and the Gullah community in “Daughters of the Dust.” They went all-in on Ava DuVernay and the criminalization of Blacks in “13th” and the Netflix series “When They See Us.”

It wasn’t all heavy. Eddie Murphy’s lighthearted “Boomerang” was on the list, and the dancers indulged Abraham’s Sanaa Lathan crush in the observant rom-com “Brown Sugar.”

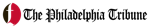

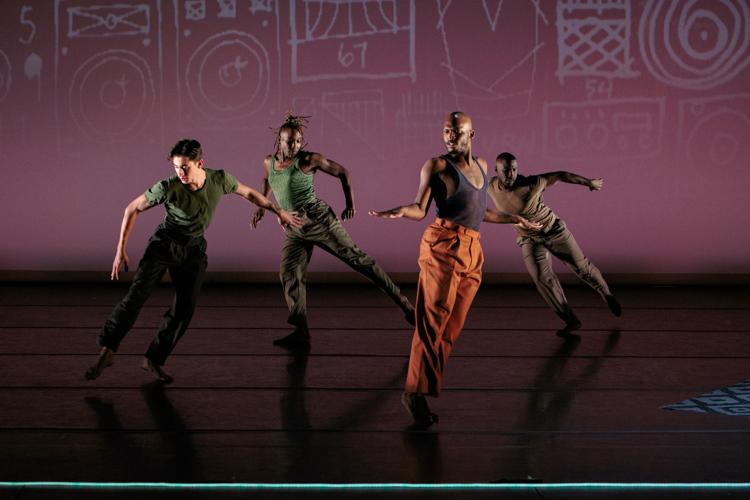

You won’t see any obvious references to these in “Untitled Love,” though the work is structured a bit like a sitcom house party. Set in a comfortable living room amid a gathering of friends, “Untitled Love” is a tone poem on the theme of affection and connection.

Recordings by R&B and neo-soul artist D’Angelo accompany the performers as they flirt, refresh their drinks, gossip on the sofa. Twosomes form and dissolve. Romance flickers, finds fuel — or doesn’t. Realistic social interactions unspool alongside smooth, lush, stylized dancing that arises naturally, out of nowhere.

Abraham, speaking recently in a video call from Boston, where A.I.M. was on tour, said “An Untitled Love” was shaped by happy memories of his 1980s youth in Pittsburgh and a desire to spotlight the sweetness of Black life, “the way that we love, centered on our joy and family and community.”

That’s the part of the Black experience that doesn’t get much attention. Abraham has spent much of his career focused on the part that does — poverty, crime, violence. “Pavement,” for example, depicted the inner city as a hidden war zone. The choreographer created it in 2012, the year before he was awarded a MacArthur Foundation “genius” grant.

Racism, shootings and the civil rights movement surface in other works. “Untitled America,” which Abraham created for the Ailey company in 2016, looked at incarceration and its impact on Black families, and “how we’re shot before we even get to a trial,” he said.

But although the 2020 police killings of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor plunged the country into self-examination surrounding racism, they didn’t necessarily prompt Abraham’s company, with its long history of unflinching work about race, to new levels of soul-searching.

“For us as a company, those weren’t new discussions,” the choreographer said. “And I wanted to be in a place where I was celebrating us, more than shining a flashlight on injustice.”

Abraham said he called his new work “Untitled Love” “because it’s not a love that, before 2020, people were acknowledging. We don’t get to see ourselves in loving spaces.”

“I want to have us be seen and heard,” he added, “and loved upon, for over an hour.”

Abraham describes himself as an outsider, though he’s an energetic talker, focused and unhurried. When he sees that our video session is about to time out, he offers to continue the interview by phone, which we do. There’s a clatter of metal in the background — Abraham reveals that he’s gotten out the ironing board and is pressing a shirt. Welcome to the glamorous existence of a celebrated choreographer on tour. Such attention to detail, and the realness of life, inform “An Untitled Love.”

“Hanging out with my mother at the beauty shop, or at the barber shop with my dad, going to the corner store — all that mixed itself in the work,” he said. “My parents’ friends coming over for card games. Seeing how they would kind of jab at one another in fun.

“I was the kid who should not have been at those parties,” he continued, chuckling. “But I was. I was sometimes too grown up as a kid; I would fix the rum and Cokes, play tonk or 500 or rummy.”

Even then, Abraham was an astute observer — destined, it seems, to be a choreographer.

“I was allowed to be in the space,” he said, “because I wasn’t trying to interfere.”

And the weekly movie group with his dancers? That was key to re-creating the specific feel of those gatherings, how relationships formed amid group laughter, or with a single glance. Watching and discussing films helped Abraham spot where the emotional beats and tensions lay.

“Everything was deepened by those conversations, especially the transitions,” he said. “Transitions are at the heart of dance-making. That’s where a lot of purpose comes in. It’s not putting your hand on someone, but it’s the space between you and that person — that’s where the vulnerability is. Is it passion, is it aggressive, is it loving? What does it mean to go from one section of music to a different energy?”

At a time when covid banished canoodling and normal socializing, watching movies allowed the dancers to zero in on how people behave in group settings, said Catherine Kirk, a 13-year veteran of A.I.M.

“It gave us time to really go deep,” she said. “To look at who we were, and say, ‘Hey, we’ve seen enough of this representation.’ To make sure we’re not being a trope. Or, ‘Hey, I’ve been walking like this, but maybe I can try this instead.’ People took agency to play with their own characters.

“I was battling with, from the jump, making sure I don’t follow this over-representation of a strong Black woman who’s hard and guarded,” added Kirk, who plays a woman who’s good at giving love but isn’t sure about receiving it. She said she took inspiration from the rom-coms, “seeing images of Black joy, and living and thriving in your community, and how that can soften someone.”

But the stage isn’t the only place for socializing. At certain venues, Abraham has designed events he calls “activations” — separate from the show — where the public can play card games with the choreographer. He wants to get people of different ages together to talk and enjoy themselves, particularly older generations.

“It serves the work, and it’s also underrated,” Abraham said. “Going to our elders for storytelling, reminding them they’re important to us.”

Such simple pleasures are on Abraham’s mind these days as he juggles outside requests and travel with his company. Increasingly, ballet companies have joined modern-dance groups in commissioning works from him. The Royal Ballet unveiled a premiere last month, and he’s creating another piece for the New York City Ballet in the fall. A.I.M. has a robust touring season ahead. Abraham said that — for a change — he’s thinking beyond dance.

“I’m trying, for the first time, to think about me,” he said. “So much of what I’ve done in making dances is, I was so focused on everyone else’s joy and needs, and I wasn’t thinking about my own. That has to be more at the center.”

What will that look like? Abraham laughed.

“I don’t know. Maybe just playing board games with friends,” he said, “and card games.”

(0) comments

Welcome to the discussion.

Log In

Keep it Clean. Please avoid obscene, vulgar, lewd, racist or sexually-oriented language.

PLEASE TURN OFF YOUR CAPS LOCK.

Don't Threaten. Threats of harming another person will not be tolerated.

Be Truthful. Don't knowingly lie about anyone or anything.

Be Nice. No racism, sexism or any sort of -ism that is degrading to another person.

Be Proactive. Use the 'Report' link on each comment to let us know of abusive posts.

Share with Us. We'd love to hear eyewitness accounts, the history behind an article.